Black and white and undead all over

Oct 1, 2021

TONY BARANOWSKI

West Virginia University NewsStart

Download the study as PDF here.

A confluence of political, economic and journalistic root causes has created a perfect storm for the resurrection of community journalism at the hyper local level, despite the prevailing and oft-perpetuated belief that newspapers are doomed by emergent technology. While the learning curve has been steep for community papers and has led to the demise of many such publications, some that steadfastly clung to traditional models of serving their communities and partners while simultaneously leveraging new tools to diversify revenue streams illustrate the relative resilience of the local newspaper and provide a blueprint for start-ups poised to fill the void left by less nimble papers, or those pillaged for profit by media conglomerates.

What follows is an examination of several such examples in the upper Midwest as derived from interviews with publishers, managers and editors of those publications identified by their respective press associations, as well as a survey of more than 50 small newspaper publishers across the United States. The purpose of this study is to help an emerging group of journalism entrepreneurs to better identify strategies, locales and models in an effort to stabilize and rebuild the proud tradition of small-town newspapering in the United States.

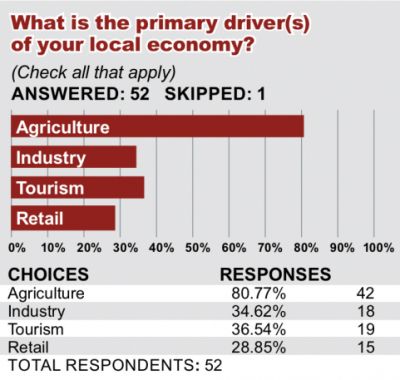

While many rural local economies have been ravaged by the rise and fall of so-called big box retail and subsequent boom of online shopping and advertising, publications that embrace the uniqueness of their local economic systems have continued to find success — agriculture, tourism and industry being the most common of those small newspapers surveyed. There is an undeniable correlation between a strong local news product and a persevering local business dynamic. While one cannot attribute the success of one to the other with any certitude, publishers and the businesses they serve are confident their shared endurance is no accident.

Communities would do well to embrace and support their local watchdogs as they struggle with the issue of how best to communicate with the public in an era of caustic social media dialogue and ever-shifting technology formats. Newspapers, even at the most local levels, continue to be the best arbiters of these new modes of communication while remaining dedicated to their traditional model.

To put it alternatively: good newspapers are as integral to the survival of rural America as just about any bellwether.

“People can’t make the distinction between ‘The Media’ and what we do,” said Julie Bergman, a 30-year veteran of community newspaper publishing in northern Minnesota. “And it hurts to be put in that same basket. But I think that the people that really matter in the communities, those that are doing something and not just observing, can see how important the newspaper is. Because the old adage goes, if your school goes, your bank goes; or your newspaper goes, your community goes, as well.”

LOCAL CONTROL, LOCAL IMMERSION

The strongest community news outlets are locally owned and managed by families or individuals with local ties that stretch back decades. That’s not an easy circumstance to replicate for a would-be publisher looking to buy or launch a news organization in a rural town, but it’s not a prerequisite, either. In fact, the common denominator is less longevity than fostering community spirit and pride within both staff-generated content and advertising in a traditional newspaper’s pages.

Jim Slonoff and his team launched The Hinsdalean in an affluent Chicago suburb in 2006 after more than two decades working for a chain that fell victim to corporate buyouts. They parlayed the buyout money into a simple business plan that yielded quick results, both in terms of acceptance and financial success. The Hinsdalean is distributed free to every household in its circulation area with little attention to online presence, which is also freely accessible.

“It was amazing to us when we opened up our office here because we were right downtown,” said Slonoff. “People walk in our door, people bring us stories or, if we’re lucky, people bring us cookies. It’s everything you dream it would be. The fact of just getting the paper in people’s hands has really contributed a lot to our success. We’re the face of the newspaper as well as the owners. In our situation with our community ... a strong local newspaper is something that people wanted and embraced faster than we thought.”

Central to the local mission of the most successful small newspapers is an observable local presence. Small newspaper chains in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, Illinois and Wisconsin all echoed this core belief in interviews. Julie Bergman dropped out of college and bought her first newspaper in Baudette, Minnesota, at 19. Thirty-five years later, that same paper remains the flagship of Page 1 Publications, which she runs with husband, Rollin. Page 1 quickly added banners under Bergman, but she remained committed to maintaining an office in each of their communities.

“We do have an office in each community, we feel strongly that that presence is needed,” Bergman said. “Each one is staffed by an average of two full-time people, and each of those people are local. In fact, almost without exception, they’ve all grown up in the communities where they’re running the papers.”

It’s antithetical to the strategy of many corporate chains and even smaller publishers that have sacrificed local presence in an effort to cut expenses.

Kurt Johnson grew up as part of a Nebraska newspapering family and considers the Nebraska Press Association a part of his extended family. Johnson left the family operation to get a journalism degree and build on his background with experience as a managing editor and executive editor at dailies. When the opportunity arose to buy the Aurora (Nebraska) News-Register in 2000, Johnson pounced on a return to community newspapering.

“I just kind of jumped in and engaged like I had in previous roles, being involved with economic development and just being very much part of the community. We devoted space to a local business page, which really tuned me into new businesses and what’s happening in the community, which was good for the newspaper,” Johnson explained.

Now 58, Johnson has begun to consider what an exit strategy might look like and says there’s no shortage of corporate suitors. But if they aren’t dedicated to journalism, he doesn’t take the call.

“There’s a lot of money out there, but if it’s somebody that just looks at it as an investment, they [downsize] the newsroom, nobody lives there local, and within a year or so you’ve got issues. Particularly if you (as the former publisher) continue to live there. That can be just a really tough scenario. So I would prefer not to go down that path.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that there aren’t efficiencies to be identified within a small publishing company, or even partnerships with neighboring communities. Most of the group publishers interviewed for this project have centralized bookkeeping, design and layout, and in some cases shared advertising sales representatives to keep overhead low. Others coordinate print schedules with fellow publishers to share transportation expenses and time on the road.

Wayward or defunct newspapers aren’t the only hub of community activities that have, at times, lost sight of building real life connections in favor of convenience and technology. Jeff Wagner helms one of the most revered newspaper companies in Iowa, Iowa Information, and its companion printing company, White Wolf Web. He says newspapers have to take the lead on community building because without those tactile relationships, the communities themselves will fail.

“One of the stupidest things school districts are doing is allowing their athletic events to be broadcast online,” said Wagner. “Because when I go to a basketball game, or football game or whatever, I create a connection with the school district; I create a connection with my neighbors. But if I can sit at home, I really don’t know what condition the school’s in, I don’t care if they get new bleachers, [and]I stop wanting to pass tax levies for my school district because I have no connection with the school district.”

Bergman calls the basic human need for a dependable local news source “the big pumpkin theory.”

“They can get their national information and their statewide information from many different sources. Who else is going to run the picture of the big pumpkin their neighbor grew that they can talk about over coffee? I’m not making fun of that! I think that’s an important kind of feature news that makes a person and people feel a part of a place. And that’s why I’m so bullish on community newspapers, whatever form or shape they take.”

GROWING, RELUCTANTLY

Many of the publishers interviewed and surveyed for this project shared similar stories about recruitment to buy neighboring newspapers, expand their footprint because of the quality of their coverage and advertising value, or just take over for another publisher who’d had enough. In some cases there was financial incentive; in others, they took risks out of a dedication to local news.

For Kris O’Leary of Central Wisconsin Newspapers, her immersion in newspapering started out of necessity when her father died suddenly in the late 1990s. She abruptly left college to help her mother, Carol, run the family business. Jay O’Leary had put the family on everyone’s radar early in the decade when The Star News made news of its own, becoming one of the first newspapers in the state to transition to fully computerized typesetting and scanning photos, ultimately moving to computerized pagination in 1992, again well ahead of the industry curve. The expansion of the O’Learys’ properties had begun just previous to Kris’ arrival on the scene.

“The week before my dad died, one of the publishers of another paper we printed at the time died. And we kind of inherited his paper to keep it going,” O’Leary explained. “And then, probably seven years ago, another publisher died, and for a year the family was asking, ‘Will you take it over?’ No, we don’t need anything more. And we ended up buying that one. We believe in community newspapers. We really want communities to have their own papers. Was the expansion done for financial gain? Probably not. But we also have two shoppers that are total market coverage, and I think that allows us to keep the other part going.”

John Galer has amassed a group of 10 banners in a small area of Illinois, equidistant from Springfield and St. Louis. As the production end of Galer’s business grew and his print customers made their exit from newspapering, they looked to Galer first as a succession plan. Galer, too, comes from a newspapering family, and the next generation is involved, although circumstances have kept them from taking the reins full-time. The Galers also have a history with cutting edge technology, although it dates back further.

“I was in the middle of my junior year in college in ‘72, and my dad lost a pressman,” said Galer, of his homecoming and headlong dive into a life of community news. “Dad had just put in one of the first offset presses in the county in the late ‘60s. The old letterpress was dying, so he went out and put a two-unit News King built by Fairchild in the basement of the building.”

That installation was an investment that would lead to decades of stability and partnership with surrounding journalism-minded colleagues. For John, though, it provided the revenue buffer he needed to continue to run his own operation at the standards to which so many others failed to adhere.

“You can’t just print your own paper anymore; you’ve got to be in print and other things, too. But if you can do that, you can probably print for about 20% less than going out to have somebody else print your paper. And so that’s why I’ve always tried like crazy to keep our production side library,” said Galer.

Wagner, on the other hand, operates his newspapers and his production facility, White Wolf Web in Sheldon, Iowa, as two separate entities entirely, which he feels helps maintain a solid business approach on the newspaper side without taking expenses for granted and keeps the production business accountable to its customers.

“Unlike most people, we’ve always treated Iowa Information, the newspapers, as a printing customer of White Wolf Web. So Iowa Information pays the same printing prices anybody else does. It makes us more sensitive to price increases if we’re also seeing them. Most people that I’ve dealt with as a printing customer that have shut down presses have no idea what the expenses are,” Wagner explained.

It’s an approach that emerged from a difficult rise for Iowa Information and the Sheldon N’West Iowa Review, which Jeff’s father, Peter, launched after a decade of successfully building clientele for his shopper in the community. Jeff described it as a nearly 15-year struggle of competition with other area publications until 1986, when both papers were nearly dead.

“My father and I went to visit a local attorney and said, ‘Hey, we’re just done. Contact the other newspaper company and see if they want to buy us because we just want to be out,’” Jeff recalled. “And the attorney said, ‘No, that’s not how this is going to work. I’ll put an investment group together, and we’ll buy half of your company. We want you to win, not other people.’”

Their fortunes turned again just a few months later upon realizing they were being overcharged for print services in Worthington, Minnesota, while simultaneously being approached by the local economic development group with a chance to build their first press facility. Within six weeks, they located both a space and a used press before the funding expired.

For Mark Rhoades of Enterprise Publishing in Blair, Nebraska, growth was a means of avoiding the hands-on press labor.

“I thought, well, if we started to grow, then I can be more in management and not have to do so much day-to-day stuff,” Rhoades laughed. “But in 1995, I think, I bought my dad out. At that time, we had three other publications. And since that time, I added another eight or nine. My target was probably within about an hour and a half around Blair because I wanted to feed our own press.”

DIVERSITY, COVERAGE, REVENUE AND PERSONNEL

Over the past few years, many American institutions and businesses have begun to acknowledge and address their lack of diversity, and newspapers are no exception. The challenge for rural media organizations is unique, however, as they seek to diversify their staff, their coverage of underrepresented communities within their individual areas, as well as their revenue streams. In many respects, these challenges can overlap for the small newspaper business model.

While most struggle to implement sweeping or even incremental change in staffing because of the often self-imposed limited pool of applicants, they are nevertheless aware of the changing demographics in their communities and continue to look for ways to better serve them. There are few minority-managed rural news organizations in the Midwest, and even fewer are minority owned. Publishers typically sought to hire a staff that reflected their coverage area and that’s almost always meant white. While representation is more of a priority now, recruiting journalists of color to small, rural areas can also be challenging. It frequently starts with the language barrier for communities that continue to see the Latinx population grow but see little engagement, even with Spanish language publication efforts.

O’Leary’s Wisconsin operation printed a Spanish language paper for a commercial customer at one time, but the project was short-lived and, she explained, language wasn’t the only cultural hurdle.

“I would say our population is half Hispanic right now,” O’Leary said. “We’re trying to figure out how to engage that population, but it hasn’t been easy. The paper we printed for one of our residents folded… Our focus is on advocating for what that community needs: housing, daycare. The newspaper plays a role in that, and we editorialize about those needs.”

Wagner’s Iowa Information cluster of papers is in a section of the state and country renowned for conservative values and a relative lack of population diversity. According to U.S. Census information, Sheldon, Iowa, is nearly 90% white with the largest non-white segment of the population being less than 5% Lantinx. The Black population is so small it hardly registers, but The N’West Iowa Review is one of the few weekly publications in the state to have employed a Black reporter and editor. Still, Wagner believes serving the minority segments of his coverage area has to be in the coverage itself.

“Are we covering the diversity of our communities? No. How do I cover that diversity? Is that by just hiring somebody who’s Hispanic? Is it about reaching out to them? It isn’t about starting the Hispanic paper, because very, very, very few Hispanic papers have ever worked … usually because they are started by a non-Hispanic trying to cover the Hispanic community,” Wagner said. “Our coverage of diversity has to be based upon names and faces. Once again, for something to be local, I have to know the name of the person in this story. So how do I diversify the community’s knowledge of each other? It’s not about how do I hire somebody with a diverse background.”

One effective way Wagner has sought to better serve existing advertising customers, boost his own bottom line and reach the minority population is by running Spanish language versions of ads, help wanted ads in particular, at discounted rates alongside the English version. The strategy has been greeted with enthusiasm from employers who know print advertising works for recruitment in rural, agriculture-based economies.

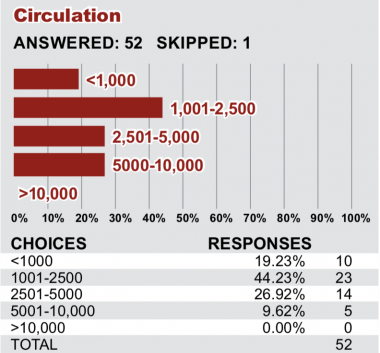

Of the 50 publishers surveyed for this project, more than 75% serve communities with a population of less than 10,000, and more than 80% identified agriculture as a primary driver of the local economy. Almost all of them (90%) considered their revenue model to be traditional, based largely upon print advertising and subscriptions. Diversification of revenue streams is another effort, even those financially successful community journalism operations recognize is a necessity moving forward, although they’ve largely stuck with the status quo.

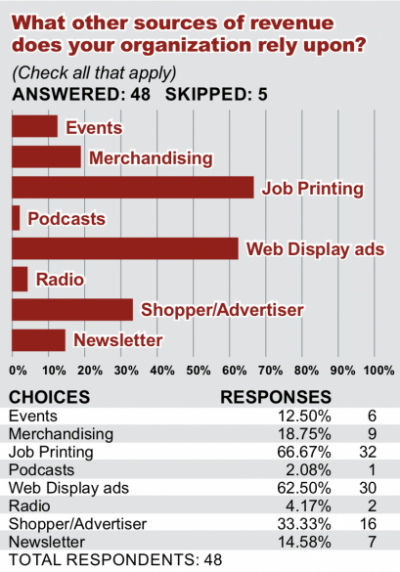

Job printing (brochures, business cards, fliers, letterhead and business envelopes) and web display ads were the only common alternative sources of revenue to top 60% of those who responded to the General Small Publisher Survey conducted for this project. There are, however, some unique efforts to bolster revenues among them, including screen printing, office supply sales and even Herbie’s Speakeasy, a liquor store in the back of the Stapleton Enterprise/McPherson County News office, a small weekly in Nebraska.

Rhoades, of Enterprise Publishing in Blair, Nebraska, is among the more adventurous and entrepreneurial of the publishers interviewed. As his son, Chris, became more involved in the family business, Mark encouraged the next generation of the Rhoades newspaper family to broaden people’s expectations of what a publishing company could do. That included digital marketing, something many small newspapers have resisted in favor of selling advertising only into their own products, but also the birth of a new company entirely, Courtside Marketing, a full-service marketing agency that branches far beyond what a typical small newspaper ad sales representative can provide.

“With The Enterprise, we’ve got boots on the street, selling newspapers. Sometimes we get the ‘we don’t do newspapers,’ but we can now go, hey, we can help you with digital,” said Mark. “We can help you if you want to rebrand your product; do you want to do new logos? You want shirts, you know, umbrellas, whatever you need. It’s amazing how many doors that opens for you if you get the roadblock on newspapers. And in some cases, it has come back around to where we’ve gotten some newspaper ads, too, because they started seeing this as the classic media consultant, instead of just the guy trying to sell you a newspaper ad. I think that’s where we need to go as an industry. You know, that’s kind of my goal is to say, we can help our businesses in any way they need — not just put an ad in the paper, which I think always needs to be part of it.”

BE ONLINE, BUT DON'T LIVE ONLINE

For two decades, the prevailing logic in media circles has been that the future of news is online. In the rush to prove that theory accurate, newspapers have repeatedly stubbed their toes, sacrificing all-important circulation numbers by offering content for free online and focusing on traffic and increasingly more invasive web banners and pop-ups to offset the shrinking print revenues that ensued. Now, finally, the majority of print newspapers have walked back those ill-fated efforts with some level of paywall, or adopted new revenue models altogether. For the majority of community papers, though, there’s no denying the power of the printed page when the lion’s share of revenue still comes from that medium. There’s also no denying the importance of a web presence for community newspapers. For many of the most successful small publications, however, the web is a necessity but not a priority.

Slonoff, in the suburbs of Chicago, said his start-up had what he would classify a bad website to start, largely consisting of contact information for he and his staff with little content and rare updates. Slonoff and his partner put very little energy into their website until nearly a decade after launch. The site is profitable, but only because the investment was and remains minimal, and Slonoff himself uploads new content the night before a new edition hits the mail. The Hinsdalean is also unique in its free distribution across the paper’s footprint, which allows the staff to dispense with the hang-ups of a paywall.

“That’s the thing I don’t get about newspapers in general,” said Slonoff, “because so many of them put so much money and resources into their websites with no return. We took the 180-degrees approach and said our money is coming from display advertising and real estate advertising. Why would we not focus on that? Facebook doesn’t bring us any money; Twitter and Instagram don’t. There’s nothing I get out of it that I know of, except we’re there. And we get a lot of likes and things and get a lot of this and comments and that feels good.”

O’Leary, on the other hand, was dead set against any kind of free access to her Central Wisconsin newspapers online since the advent of the internet. She also pointed to segments of the community she serves that remain dependent upon print.

“It wasn’t like we were ever hesitant to go into it. It’s just as things were evolving, it was like, I don’t think this is going to be a great business model because I don’t understand how you’re going to make money off it,” O’Leary explained. “Especially in a small rural area like ours. We have a very large Amish and Mennonite population. So the web there doesn’t work at all for their needs. So they’re very much print people, which is good for us. And we have a large Hispanic population. Our website has never been a financial gain. For us, it’s pretty much there because you need to have a web presence.”

That doesn’t mean digital is an afterthought for O’Leary, Slonoff or any number of other small papers that have found ways to better tell stories and, yes, even monetize content online. At a time when many papers are recognizing the struggle of competing against social media for timeliness, Johnson, of the Aurora News-Register in Nebraska, says his sports staff has taken a new tack as it relates to Friday night football coverage for the successful hometown Huskies.

“Every game we’re there, we take several hundred photos, interview the coach, interview a couple seniors and we pull video highlights and put a three-minute video together that goes out on our YouTube and obviously Twitter,” said Johnson. “We connect with the local telecommunications company; they have a local TV channel that they were not having much success with. So they basically gave us the keys to the content of that local channel. And we sell ads on that. So those videos then we post to TV.”

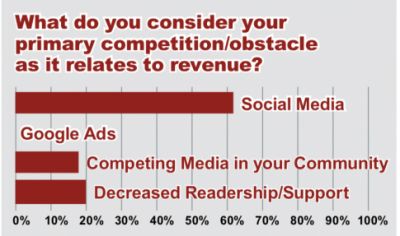

Others, like Rhoades, are having success with email newsletters. His clutch of papers in Blair, Nebraska, release their newsletters on non-publication days, promoting the content that will be in the next edition of the print product or rehashing what may have been missed the day before. He said readers have to opt in to receive the newsletter, but they use those email lists in other promotions and contests for better engagement. Bergman called her E-edition, a collection of PDFs of the print paper available online, wildly popular in the northwoods of Minnesota. All publishers interviewed were in agreement on one thing: while Facebook posts bring traffic, social media rarely translates to anything monetarily positive for their small businesses only difficulties in public relations. More than 60% of publishers surveyed identified social media as the primary competition/obstacle as it related to revenue in their coverage area. Decreased readership and competing media were the next most popular responses to that question, still lagging 20% behind social media even when combined. Google ads didn’t receive a single vote.

“As a reporting tool, social media is a gift to reporters, because you know what the community is talking about,” said Bergman. “But I’m wearing my publisher hat all the time, and you can do wonderful things for the community, but if you don’t make a profit at the end of the day, and your doors shut, you haven’t done anything for your community. I want one good hire that would take over that piece and would bring us to a different level. But my question is, how do we pay for that?”

DEFYING THE TRENDS

The overarching common thread across interviews with some of the Midwest’s most successful and innovative publishers is a frustration that, while they have persisted and, in many cases, thrived, they have also been largely ignored by industry leaders and stained by the sins of mainstream media. Or at least the forecast of its impending demise, constantly battling the idea that “newspapers are dying,” even to their most ardent supporters.

“One thing I think the industry needs to do is stand up for ourselves a little bit better,” said Rhoades. “We’ve never really fought back as an industry very well when you hear that ‘you guys are dying’ message. We kind of laugh it off.”

Rhoades isn’t laughing anymore – recently calling on the carpet a state lawmaker he had always viewed as an ally for introducing legislation that would pull a vital source of revenue, legal notifications, from Nebraska’s newspapers.

“He said ‘I don’t think we need to put a public notice in about the meetings because nobody really reads newspapers anymore anyway,’” said Rhoades. “There would have been a time I would have gone, oh, I don’t want to make waves. But we just have to stand up. I wrote and said, people pay for us, people get upset if we screw it up. We run your column every week! We’re not dead. We’re different. But we’re not dying.”

So well documented are the cases of newspaper failures, closures, layoffs and the like that the belief they were unanimously on borrowed time trickled down to the community level, while the damage that caused those collapses never did. Yes, many community papers have also folded, especially those enveloped by larger, corporate parent companies. In their wake, however, new publications and new models have risen, or reluctant news leaders like John Galer and Kris O’Leary have been pulled in.

“I think the perception for people is that weekly newspapers aren’t real newspapers; it’s just your weekly gossip or whatever. But we know people read it,” O’Leary said. “They’ll claim that they don’t, or they won’t subscribe because you’ve made them mad for whatever reason. But they sure know what’s going on when their name is in the newspaper. And they’re calling and saying, ‘Hey, can you take me out of the police report?’”

The secret, if there is one, is maintaining positive momentum in the communities you serve, Kurt Johnson says. And it’s very much an old-school approach.

“If the tide is rising in your community, the newspaper is going to do fine. So I just wanted to be part of that process,” Johnson explained of the many hats he wears in Aurora. “Just some of my own personal philosophy my dad, Loral Johnson, raised me with; he was very much a community leader and did so with a humble servant attitude.”

That frequently means being the driving force behind issues — like hospitals, schools and banks that Bergman grouped with newspapers as the harbingers of community vibrance. Sometimes those efforts are public editorials supporting a cause. Many others, however, are networking with community leaders, advising them on strategy and, above all, earning their trust and faith that what is in the best interest of the community is in the best interest of its local news provider.

THE MAGIC BULLET

The purpose of this project is to identify strategies that best position the next generation of publishers for success. While some trends were positively identified, the conclusion derived is there is no single roadmap to success in publishing at the community level. The news is better than that; there are a plethora of plays to call and strategies to employ to deploy or revive a newspaper. The common factors that have kept community journalism successful are frequently:

- A general dedication to the news product, sometimes to the financial detriment of the paper and its stakeholders

- Maintaining and defending the value of both the news and advertising products of the organization

- Being agile and experimental enough to diversify revenue

- Recognition that the good of the community as a whole supersedes all else

There are other advantageous factors. Local ownership and management with insight into the history, personalities and economy of a community are almost always beneficial. Geography matters as much as competition or lack thereof; the days of multiple competing news organizations thriving in a small community are gone. While competition may sharpen the skills and will of a news team, sharing limited pie in a limited area is more likely a recipe for failure than better quality journalism. Identifying a hub of established and stable businesses that have a history of teaming together to accomplish big goals is not just a harbinger of stability for a good news organization, but a barometer of how well a strong newspaper might be embraced in helping to execute those big picture efforts.

“I work a lot,” said Jim Slonoff, a one-time castoff of the corporate papers of suburban Chicago, “but I’m probably working less than I did in my previous job. And I’m certainly enjoying it 100 times more. Not to brag, but financially we’re solid. People really want to be connected with their community and with each other. Churches provide that; other institutions provide that. But we really bring everything together in one place. Our motto is ‘Community journalism the way it was meant to be.’ Just look back and see what used to work because that’s what, believe it or not, in this overly connected world, people still want to know what’s going on next door and down the street.”

Tony Baranowski spent the past year as a fellow in the NewStart program at West Virginia University, earning a master's degree in Media Solutions and Innovation. Baranowski is a lifelong Iowan who has worked for newspapers his entire professional career. He’s currently Director of Local Media for Times Citizen Communications in Iowa Falls, a small but diverse multimedia company in the north central part of the Hawkeye State. He can be reached at tonyapb3@gmail.com and on Twitter @tonyapb3. The NewStart program identifies and trains the next generation of media entrepreneurs, with a focus on rural community news organizations across the country, including for-profit and nonprofit established publications and startups.