N.C. family with seven decades of courage, integrity and tenacity honored with Tom and Pat Gish Award

Aug 1, 2021

A family that has demonstrated courage, integrity and tenacity at its twice-weekly newspaper in North Carolina over three generations is the winner of the 2021 Tom and Pat Gish Award from the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues.

The Thompson-High family has owned The News Reporter in Whiteville since 1938. In 1953, it and The Tabor City Tribune, also in Columbus County, were the first weekly newspapers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for a successful fight against the Ku Klux Klan.

Since then, The News Reporter has continued to show courage, integrity and tenacity by holding accountable local public officials, especially those in the criminal justice system, despite significant financial adversity, reader and advertiser boycotts, personal attacks and threats against family members’ lives; and taking smaller profits in order to better serve its readers.

“The News Reporter also provides an example of how a community newspaper can adapt to the digital age, still perform first-class public service and even extend its reach beyond its home county,” said Al Cross, director of the rural-journalism institute and extension professor of journalism at the University of Kentucky.

The News Reporter’s print circulation is 6,000; its website, https://nrcolumbus.com/, gets 80,000 unique visitors a month. It has secured philanthropic funding to launch the nonprofit Border Belt Reporting Center, which will provide analytical and investigative reporting to residents in three neighboring counties served by understaffed local papers.

“The Thompson-High family represents the very best of community journalism. It is a courageous family of journalistic crusaders, entrepreneurs and evangelists,” wrote nominator Penny Muse Abernathy, who recently left the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for Northwestern University. She has used The News Reporter as an object example in her groundbreaking research on community newspapers.

“In an era when the owners of many community newspapers have sold out to big chains or closed their doors when faced with adversity, members of each generation pursued strong public service journalism, even as they adjusted business strategy and mission to provide residents in their region with the critical local news that feeds our democracy at the grassroots level,” Abernathy wrote. “The longstanding advocacy of [the] Thompson-High family is a testimonial to the difference a small, courageous independent newspaper can make in the history and fortunes of the community and the region where it is located.”

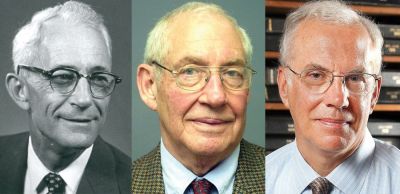

The News Reporter’s publisher is Les High, who succeeded his father, Jim High, who succeeded his father-in-law, Leslie Thompson. In the early 1950s, before the civil-rights movement gained much traction, Thompson defied advertiser and reader boycotts — as well as personal attacks and threats on his life — to wage, with Editor Willard Cole, a two-year struggle against the Klan, which had infiltrated local police departments. News stories and front-page editorials documented and excoriated Klan beatings, floggings and drive-by shootings, ultimately leading to the arrest of more than 300 reputed Klansmen and the conviction of 62, including the Fair Bluff police chief. The News Reporter and The Tabor City Tribune, also in Columbus County, received the Pulitzer for Public Service in 1953.

Jim High wanted to be a veterinarian but became publisher when his father-in-law died suddenly in 1959. He aggressively covered the criminal justice system and received national notice for filing suit to overturn a gag order, a device that courts around the country were using to close sensitive trials to the public. The News Reporter won the case — and almost all the others it has pursued.

Les High has continued his father’s approach, taking on officials who hide public records, cover up problems or abide corruption, although legal action is costly and risky and the paper’s profit margins have dropped into the low single digits. He recently put together a coalition of two local TV stations and another newspaper to sue the county sheriff for withholding incident reports in response to stories and editorials in The News Reporter that exposed conflicts of interest and bullying by the sheriff’s department. High, his editor Justin Smith and reporters endured social-media attacks, profane harangues and veiled physical threats, reminiscent of those Leslie Thompson got when he took on the Klan. This campaign led to subscriber cancellations, depressing an already fragile bottom line. To help cover the cost of the suit, The News Reporter got a loan of $5,000 from the trade group America’s Newspapers, which the paper repaid when a judge awarded reimbursement of $30,000 in legal fees as a punitive measure.

That impressed Ben Gish, publisher of The Mountain Eagle in Whitesburg, Kentucky, whose parents’ names grace the Gish Award. “As impressive as the entirety of their nomination is, they get extra points from me for making sure they repaid the $5,000 loan,” Gish wrote. “That occurring at the same time the papers owned by the large corporations reap all the benefits of the Report for America-type programs speaks volumes to me.”

Threats to The News Reporter’s bottom line are nothing new. In the late 1950s, Jim High “discovered the paper was on the financial brink” and took a gamble, Abernathy wrote. “He built a new plant and purchased one of the first offset presses in the state. To reverse the slide in circulation and advertising, he committed to ‘providing better coverage than a community of this size might expect’ by adding reporting staff.”

Les High faced a similar challenge in the Great Recession, “when profit margins fell from around 20% to the very low single digits, as print advertising from local businesses collapsed,” Abernathy wrote. “Instead of hunkering down and laying off staff — or selling out to a large chain — Les chose to invest in digital transformation.” He persuaded his sister Stuart to return to Whiteville, and she not only improved the paper’s digital presence but started holding community events. In recent years, Les’ wife, Becky, and daughter Margaret have joined the effort.

“In 2018, when the paper posted an unprofitable year, the family nevertheless doubled down on its digital investments — creating a metered paywall, redesigning the website, introducing a mobile app and initiating a 24/7 news cycle to post stories and videos on the newspaper’s website as soon as possible after an event occurred,” Abernathy wrote. “The paper currently hosts a weekly video news report, two email newsletters, several major community events a year and an in-house digital advertising agency that serves local businesses. Despite slim or nonexistent profit margins, Les has also invested in the newsroom, which has seven journalists. In 2020, even as the lawsuit against the sheriff weighed on the bottom line, The News Reporter added a reporter to cover the pandemic and the 2020 elections.”

Les High is “an example for other publishers who may lack the courage and conviction to invest for the long term,” Edward Van Horn, retired executive director of the Southern Newspaper Publishers Association, told Abernathy.

He is also one of a dwindling number of independent newspaper owners, but rather than draw a defensive line around Columbus County, he is expanding to Scotland, Robeson and Bladen counties with his nonprofit Border Belt Project and online publication, Border Belt Independent (https://bit.ly/2TE0L7S). Along with Columbus, “These counties along the South Carolina border are among the poorest in the state, and a majority of residents are members of racial or ethnic communities, including the largest population of Native Americans east of the Mississippi,” Abernathy wrote. “All three adjacent counties are currently being served by under-staffed local newspapers. Collaborating with reporters at these newspapers, the center will cover topics – such as the environment, health, education, public safety, economic development and local governance – that will affect the quality of life of current and future generations of residents.”

It will provide its reporting at no charge to the other papers. “We’re not competitors,” High says. “We’re partners.”

“I can't think of a better model for an independent, family newspaper,” said Jennifer P. Brown, who is co-chair of the rural-journalism institute’s advisory board. “The Thompson-High family's commitment to serving the community is so hopeful, and shows what is possible.” Brown, who was editor of the Kentucky New Era in Hopkinsville when it was family-owned, publishes the digital Hoptown Chronicle.

The Tom and Pat Gish Award is named for the couple who published The Mountain Eagle for more than 50 years and repeatedly demonstrated courage, tenacity and integrity through advertiser boycotts, business competition, declining population, personal attacks and even the burning of their office by a local policeman who state police believe was paid by coal companies.

The Gishes, who died in 2008 and 2014, respectively, were the first winners of the award in 2005. The other winners, in chronological order, have been the Ezzell family of The Canadian (Texas) Record; Stanley Dearman (former publisher, now deceased) and Jim Prince (publisher), The Neshoba Democrat, Philadelphia, Mississippi; Samantha Swindler of Portland, Oregon, for her work at the Jacksonville (Texas) Daily Progress and the daily Times-Tribune of Corbin, Kentucky; Stanley Nelson and the Concordia Sentinel of Ferriday, Louisiana; Jonathan and Susan Austin, publishers of the now-defunct Yancey County News in Burnsville, North Carolina; the late Landon Wills of the McLean County News in Calhoun, Kentucky; the Trapp family of the Rio Grande Sun in Española, New Mexico; Ivan Foley of the Platte County Landmark in Platte City, Missouri; the Cullen family of the Storm Lake (Iowa) Times; Les Zaitz of the Malheur Enterprise in Vale, Oregon; Ken Ward Jr., then of the Charleston Gazette-Mail and now of Mountain State Spotlight; his mentor, the late Paul J. Nyden of the Charleston Gazette; and Howard Berkes of NPR; and the late Tim Crews, who was editor-publisher of the Sacramento Valley Mirror in Willows, California.

The Gish Award will be presented Oct. 28 at the annual Al Smith Awards Dinner of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the Marriott Griffin Gate Resort on Newtown Pike in Lexington, Kentucky. The dinner was not held last year, so Tim Crews’ widow, Donna Settle, will receive his award, as well. The keynote speaker will be Chuck Todd of NBC News.

The dinner also honors recipients of the Al Smith Award for public service through community journalism by Kentuckians, which the institute presents with the Bluegrass Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists. The 2020 winner is Becky Barnes, editor of The Cynthiana Democrat, who set a national example by sending an extra of her paper to every address in the county when it had the state’s first Covid-19 case. The 2021 winner is WKMS, the public-radio station at Murray State University in far Western Kentucky, for being “a model for courageous public-service journalism, especially at a time when citizens are looking more to public radio to fill voids left by shrinking commercial media outlets,” Bluegrass Chapter President Tom Eblen said.

Details about the dinner will be available soon on the institute website, http://www.ruraljournalism.org/.